‘Dig where you stand’ is an eternal piece of advice when it comes to writing. Most likely, you’ll craft the best stories in environments you feel comfortable in. Zenopolis would never have come into being had I not spent time with the locals in Seville. My debut novel Ensamma tillsammans (Alone Together) would have lost all credible detail if I hadn’t first spent a year on the psychology programme at the Karolinska Institute.

A piece of advice fewer writers give, but which extends naturally from the first, is to catalogue your worlds, then combine them with your story ideas. It can be hard to spot a potential novel in a local newspaper internship (more on that later), or in witnessing the dotcom boom but being too young to take part. Until, that is, you begin to see yourself and your surroundings.

I did start a web agency, but I was so young we missed the big train, and that still nags at me. Luckily, literature exists, where failure often turns useful. Which means: you always win.

This is chapter three of Naïveté Travels.

(Missed the first chapters? You’ll find the full series here.)

Welcome away ꩜

Jörgen Löwenfeldt

✦ Naïveté Travels: Act Three ✧

Eventually I dialled the number. Several times, in fact, but it was out of service. Whether I called in the morning, during my lunch break at work or in the middle of the night, the result was always the same: a dead signal. Other people don’t give up when things get hard; they carry on and take what they want. When the girl breaks up with them, they show up with a guitar and a bouquet of roses and wait on the steps until she opens the door. I just accepted the situation, gave up before anything was even properly lost.

If I had barely given Jan Berger a thought before, I now began, in my solitude, to think of him as an older brother. In my teens, I had followed him from a distance, as he travelled, built a career and became the person I wanted to be: worldly, charismatic, assured. That last point in particular had always been difficult for me, getting others to accept my presence, having girls describe me as anything but kind, hearing colleagues call me something more than nice. It was as though I was transferring the loss of my girlfriend into another context, as if it had been him who slipped through my fingers, not her. And in truth it applied to both, since it seemed part of my personality to regret, but rarely to learn.

One Saturday, instead of going to the pizzeria, I went down to the basement storage unit. In the nostalgia box were the old magazines from my internship. I began leafing through them, with the same self-destructive instinct as if I had been revisiting old holiday photos of me and my ex.

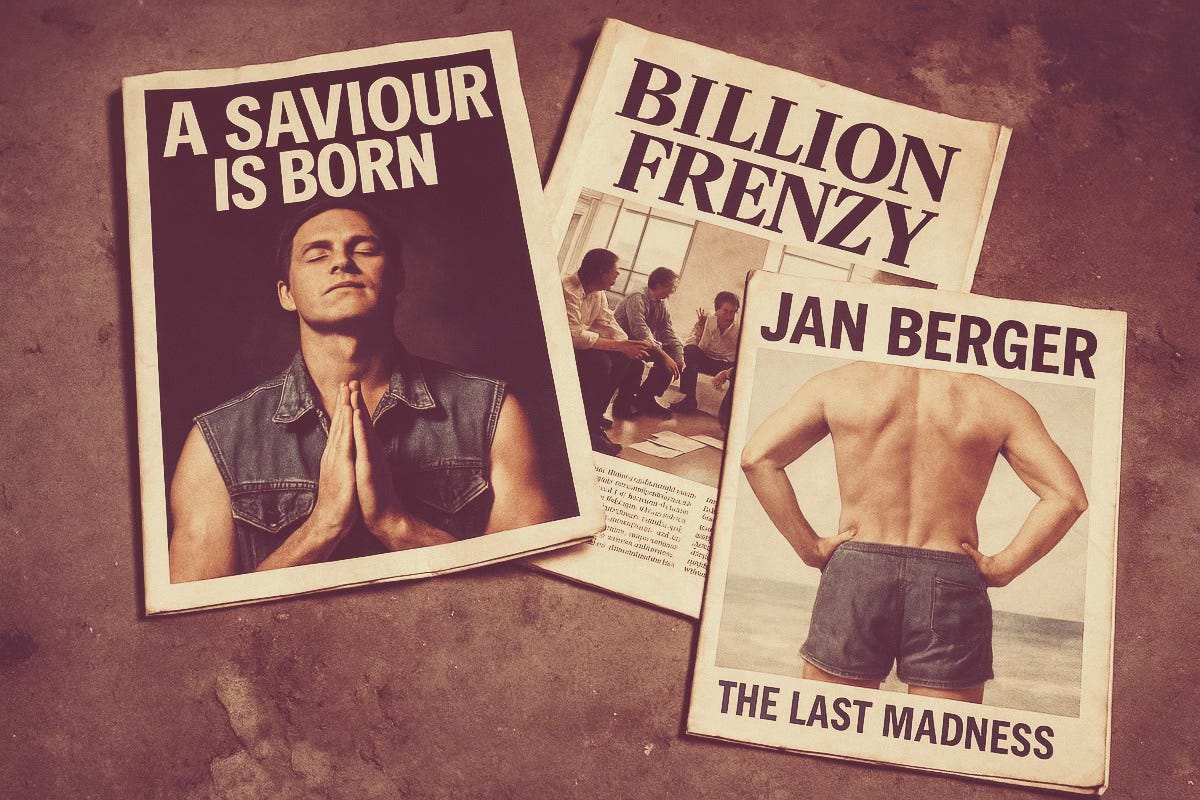

“A saviour is born,” read one cover headline, featuring the great Jan, wearing a denim vest, eyes closed, hands pressed together, chin lifted slightly as if to draw nearer to his supposed father, the Lord. Another cover needed just the words: “Billion frenzy.” According to the journalist, every Swedish investment firm was fighting for a stake in Clockwork, crawling into the office’s cushion room and being forced, barefoot, to prove their brilliance to the CEO in Tarzan underpants. When he was at his most childish and sadistic, he would make them play charades to get his point across. Other times, they had to use crayons in sketchbooks. Anonymous bankers in the article claimed it was all nonsense and degrading, but at the time the spirit of the age played right into the hands of the dotcom boys. It was different now and everything was going to be even more different. The game had to be played when billions upon billions were once again on the table.

In one of the magazines, one of the last before the closure, I spotted my byline next to a social write-up from a clearance sale of Clockwork’s office equipment. The freefall could hardly have been rendered more clearly, yet even here Jan Berger managed to be at the centre, almost as if he had won. Others, more calculating entrepreneurs of the business-school variety, had sold their holdings well in advance of the crash and fled to Thailand or Dubai. But Jan had held on to his stocks all the way to the bottom. Now he stood in the middle of the empty office floor, letting the bidders place offers on what remained: first the furniture, the lighting, the pinball machines and computers, and finally, as a finale, the CEO’s personal effects.

Among the items sold were his wristwatch (a Seiko), shoes (worn-out Pumas), and even his swimming trunks, still faded from the legendary party in Honolulu. Altogether, his sparse collection of belongings fetched around four million kronor, during an afternoon that later became known as The Last Madness.

He was able to leave the office that evening with plenty of money in the bank, but no clothes other than those on his back, and no place to sleep, having also sold the hammock that, according to legend, had been his only real home, even accompanying him on overseas visits to venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, Tokyo and Manhattan. My article was probably the very last to include direct quotes from Jan Berger. He referred to Buddha, who had apparently said: “To keep the body in good health is a duty, otherwise we shall not be able to keep our mind strong and clear.” And when I asked what he would do now (or maybe it was someone else at the event, I can’t remember) he said: “The same thing I’ve always done. I’ll move forward, and inward. There is no other way.” Then he wandered out onto Stureplan, having left his access card at the empty reception desk, blended into the crowd, and vanished. A few weeks later, an insurance company moved into the premises and the world became normal again, dull and predictable.

A little over half a decade had passed. I sat cross-legged in the basement and wallowed in events that weren’t particularly distant in time, yet still belonged to another millennium. A time in my life when I genuinely believed I could reach the top, when I thought that by now, at their age, I would be doing just that: commanding a crowd with my presence, raising a single finger to quieten a room. Men like him never worried about what their families thought of their lifestyle. It was the families who had to adapt to the patriarch.

What would he have done in this situation? He wouldn’t have cared in the slightest about anyone but himself. But if he had given me, me specifically, a piece of advice, it would have been: Then go to Belgrade. Finish what you started, you hesitant fool.

The fact was, I had used up all my holiday allowance helping the girl move, and I had lost a few days by not taking them in time, so another trip didn’t seem realistic that calendar year. Jan wouldn’t have cared about that, but he and I lived by different rules.

Besides, a miracle occurred, one that knocked me out of joint again.

It had been two months since she left me when she suddenly wanted to meet and talk, without giving any particular reason. Just talk. She came to me, made her way to the lunch restaurant near the Environmental Protection Agency, didn’t even complain that I took too many napkins or poured my coffee too early (so that I drank it cold, which according to her was practically sacrilege). I understood something had changed, that the pendulum had swung in my favour. She murmured, eyes lowered, hands searching across the table for mine:

“I’ve had a change of heart.”

She then explained how she had been thinking, without actually saying anything at all. It had been just as I had suspected. She had been living with her parents, growing more miserable by the day. The deep male voice I had heard, she said, belonged to a second cousin visiting from Östersund, and even though it was not a very convincing explanation, I chose to believe her. I too wanted to continue and see where it might go. Above all, I wanted to leave behind my downward spiral toward the abyss of bachelorhood.

Her best friend had got engaged, and now I began to understand her thinking. I was, after all, a safe bet: a flat, a steady job. I had a mild temperament, had never harmed a soul, and could converse about almost anything without asking difficult follow-up questions. No one could keep a conversation going like I could. From a distance, I seemed more and more like a catch, or so I interpreted it. That might soon change, but then was then. Now was now.

“I’ve been thinking too,” I said, which was true. I then promised how I would do better this time. I would take more initiative, listen more attentively, and empty the dishwasher as soon as it was done, even if the plates were still hot. I had also been thinking about having children, I said, because it felt like something I needed to say if we were to move forward rather than just go over the past.

“Oh really?” she said, raising her eyebrows.

“I mean, sometime in the future. Not now, obviously. We’re basically kids ourselves.”

“Yes, I live with my parents,” she said, grinning.

“There’s always space at my place, or I mean our place, or, you know what I mean,” I said.

“Well, of course I want to be a mum someday,” she said.

“Of course you do,” I said, adding, “And what a good mum you would be.”

And just like that, we were a couple again. A couple standing on far more porous ground than before. If I had once been unsure of my position in the relationship, I now had to tread carefully and more or less perform a role in every waking moment at home, terrified that she would change her mind and leave me again for that man with the dark voice, the one I imagined to be a violent lover.

But I couldn’t think like that. I simply refused to continue exploring the darkness. I pushed aside everything that felt negative or harmful and convinced myself to focus on the brighter side instead. I was no longer alone. I had a girlfriend and she wanted me. That was more than most could say. And unlike many who have lived on this planet, I had never known famine or war. There were no valid reasons to show discontent with anything. Except, perhaps, that I now woke up every night at four and couldn’t get back to sleep, because my body filled with a kind of impossible stress. I would sit in front of the television and watch late-night programmes until she woke up and everything began again.

The routines. The performance that is life.

…

Thank you for reading.

– Jörgen Löwenfeldt ✦ jorgenlowenfeldt.se ✧ bagatellerna.se ✦

This dispatch was sent to five hundred and eighty-nine readers. If my writing resonated with you, consider sharing it with a friend who might feel the same, or leave a comment.

A warm thank you to the eight monthly sponsors of The Bagatelles: Billy, Björn, Mafalda, Monica, Anders, Johan, Paul and J Draffin. Your belief in my work keeps me going, and as a paid subscriber you have access to all content, including my literary diary and the novel Zenopolis.

You can send questions, comments, invitations, links and more to jorgen@saltsea.se. I read everything you send me (and I like surprises). After all, communication is the whole point of publishing.

Read all three chapters. From the first time I was exposed to your writing… you have phrases which emerge… apart from intriguing plot lines and keen success integrating “world catalogues”… that simply connect genuinely and evoke analogous emotions, recollections, yearnings and self-flagellations… kinship producing interest in the outcome.

“because by the time I returned, I had to be someone. Otherwise, what was the point of running away?”

“But I couldn’t even choose the road to ruin. I just stood there, awkward and still, watching like any old nobody: a bit too average, a bit too plain, a bit too quiet. A bit too wrong.”

I said it earlier and must again… I’m hooked.

I loved when the chaos paused and allowed emotion to surface. The way madness made space for clarity felt truly genuine and reminded me that even in our wildest moments, there is grace worth savoring.