The second chance at a first

Featuring: The Maybe Man, Charles Swann ✦✧ The Secret Pianist ✦✧ The Atheist

A bagatelle can be a short piano piece, a trifle, or a story without a true beginning or end. I began writing them in 2009 on the back of envelopes. Those envelopes became an anonymous blog, the blog turned into an Instagram account, which led to a published novel, then took a U-turn toward a newsletter, and now Swedish has become English. And I am new again — for a second time. Very seldom do you get a second chance at a first. I will try to treat this gift simply as a gift, with care and gratitude.

Warmly,

Jörgen Löwenfeldt

✦ The Maybe Man, Charles Swann ✧

He had set himself the task of writing a text each morning, with no demands as to quality or word count, simply a text. He would start at 8:15, and twenty minutes later it would be finished. The procedure required little more than a regular sleep routine and one additional ingredient: the idea itself. Often he managed to catch hold of some small detail the day before, which he could later expand into literature, such as a snippet of conversation about washing a Mercedes, or a hostel receptionist with a fondness for Bonnie Tyler. On other days, he would need to draw inspiration from the morning paper, allowing an obituary or short notice to steer his thoughts in a productive direction.

But then there are mornings like this one, when he must close his eyes and let the previous day ripple through his mind, in the hope that the trawling will bring something to the surface. And indeed there had been a previous day this time too, he notes, lying on the sofa. All thoughts carry equal weight as they drift past: he is going to be an uncle, an intense chat on WhatsApp, a barely cleared walk along the Hammarby canal, glasses of wine with the calligrapher, the discussion about the evolution of biathlon (like combining a 100-metre sprint with darts, they had said).

Yet he lingers on Charles Swann, the fictional man to whom Marcel Proust devotes such care in the first volume of In Search of Lost Time. From the outside, this worldly Swann might easily be viewed as a playboy, since there is scarcely any other definition of such a person than precisely the type Swann represented, and yet, like a typical fin de siècle maybe man, he could never help but lose himself in the people he sought out. There was a barrier somewhere, but not in the encounter, not in desire or longing. Beyond words, which of course were never to lead to any lasting arrangement, there was always a spark of truth between Swann and his lovers, something noble and tender. Perhaps only for a fleeting second, but that was his secret: where other playboys played the game, he played it with heart and soul, always with a large measure of naivety concealed beneath his more prominent dandyism. He sought an embrace as much as he sought a truth, his truth, when he pursued maids and duchesses alike, never distinguishing between people, for he followed feeling, and feeling knows no class. And who can judge a feeling if it has been shaped without the interference of thought? It simply is, like a magical presence within us.

Charles Swann sought his embrace without truly understanding his need. All women’s bodies merged in his imagination when he gave himself over to such fantasies, but calves, hips and shoulders were transformed into the needs of warmth, softness, glow and tenderness. All of it beautiful and noble, even that which the world might have dismissed as greedy desire. No one accuses a connoisseur of eating food that is too exquisite, he may have comforted himself, if he ever felt branded as seedy. Until he meets Odette, who is nothing like the others, and for whom he feels no initial attraction at all, but she is Odette, and therein lies the difference.

The intellectual and idle playboy Charles dashes through his days in pursuit of experiences like a manic user of Tinder, when, as it turns out, he needs only a single experience, a truth and no more, an experience the relationship coaches speak of in every podcast on the subject. Dare to choose your path, Charles, and the path will choose you.

It is on this that the writer finally reflects as he sits down to write, and he writes.

✦ The Secret Pianist ✧

Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A minor forced its way into my flat one evening. The sound waves came from a neighbour, who played with a light, almost nonchalant touch. At first I was irritated by the intrusion, but after a few bars I realised that the player had considerable talent, though clearly not classically trained, perhaps a jazz musician or an autodidact. Maybe that was why I found the music so moving.

There was a true originality in it, with the fingertips landing on the keys with languid timing, in a just-in-time manner, before they slid off the piano like tears. Other passages were played boldly, with a childlike energy, as though the piece were being played for the very first time. Whether it was beginner’s luck or genius was hard to say, as was the age and gender of the pianist. They might just as easily have been a twenty-year-old with a spirit of discovery as a retired musician who had given up on rules.

I listened every evening. It soon became a ritual, with chamomile tea in a porcelain cup, a soft blanket, and the music, that sweet, flowing music, so imprecisely precise, with missed notes and clumsy slips between the keys, but that was part of it. The music had life, it swept into my daily existence and enriched my soul.

Before long, I found myself looking at my neighbours in the stairwell in a new light, trying to work out which of them might be the divinely gifted pianist. The lady with permed hair? The sprightly, round fellow? The child always chatting on a mobile? I began watching their fingers after a while, as their faces offered no clues, searching for slender feelers, perhaps slightly angular knuckles and joints, but everything about my neighbours spoke of ordinariness. No one seemed capable of playing in that almost-paralysed manner, always just a little too late but still on time. An anticipation arose between each keystroke, as the music was woven through the air by this virtuoso who, each evening, seemed to make a confession to the rest of us.

A friend with an orchestral background came to visit, to help me put together some sort of phantom profile, drawing on her knowledge of pianists. She was nearly as impressed as I was, though the occasional wrong notes bothered her, and after half an hour of listening she said it was probably someone who had never performed in front of others, an unpolished pianist. Probably a little older, she added, as younger players would already have had their quirks smoothed away. I thanked her for the insight. As she left for the evening, she said, Why not just ask around? I began to breathe heavily and said nothing, mumbling vaguely to suggest that such things weren’t easy for me. Then put up a note? she suggested. A mad idea. How would I appear to the others?

Still, I agonised over the wording, which I pinned to the noticeboard: a rambling message about my slender Hoffman piano designed by Carl Malmsten (I’d realised it was something special after a previous visitor had tried to exchange their concert grand for it), and I asked whether anyone in the building might like to use it, as I myself did not play and its tuning was beginning to drift. I thought that a talented pianist wouldn’t pass up such an opportunity, and each evening I awaited an unexpected visit from my musical benefactor, who would make a very modest entrance, approaching my instrument with gentle steps, sitting down on the stool and slowly unfolding their fingers, before placing them on the keys — each stroke a little heavier than usual, as I had come to understand — and they would appreciate that the instrument had a bit of temperament, that it resisted slightly while being filled with the sound waves which stirred all my emotions. But no visitor ever came.

Instead, the music fell silent and never returned. I remember it now, many years later, as one remembers a particular taste or a moment of euphoria, in a precise place in the mind to which I can always turn when life feels petty and meaningless, when every particle in the air could, in fact, be imbued with spirit.

✦ The Atheist ✧

The apartment actually burned down. After all her warnings about the gas, it caught fire. Just a small lapse, just a tiny spark. The bookshelf erupted in a veritable fireworks display. The carpet glowed at its corners. And there I lay in the sleeping alcove, surrounded by flames, already rendered unconscious by the toxic smoke. I murmured softly like a child, or like a fully contented cat, wrapped up in myself and the duvet.

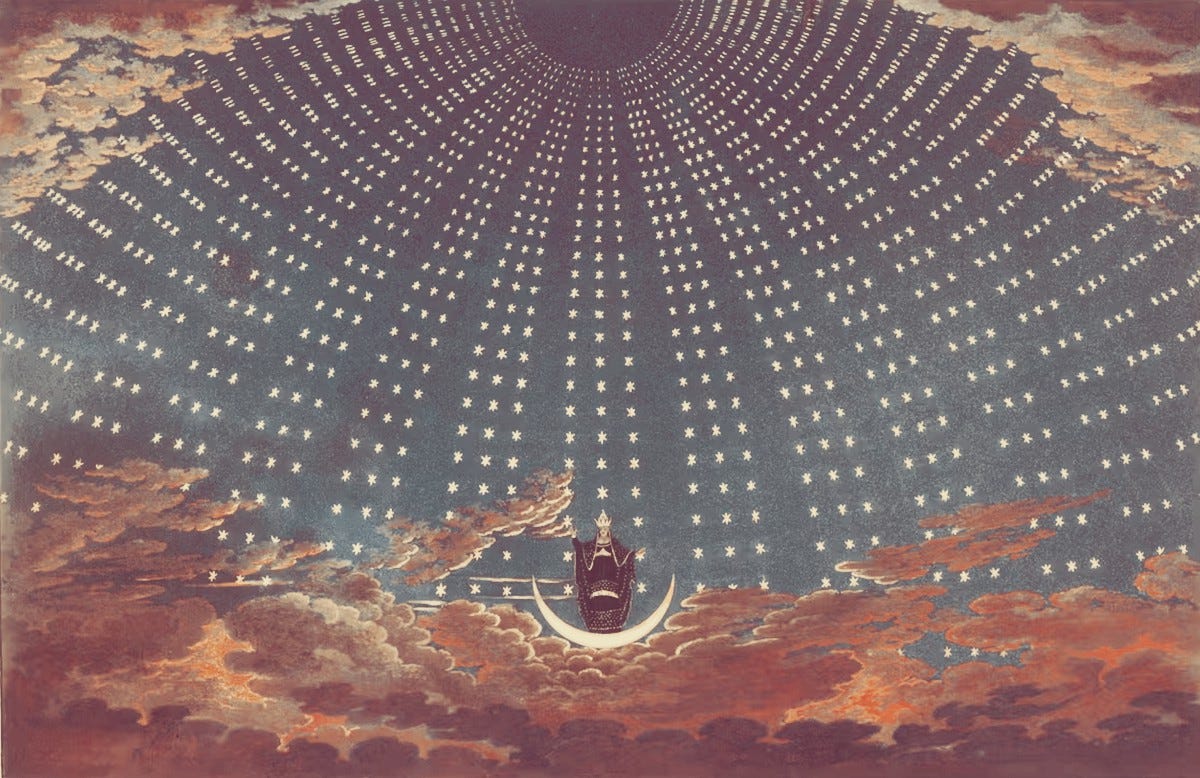

It was so strange. I had never believed in such things, I had devoted a lifetime to arguing for the opposite, for rationality, for what I could comprehend from the little I already thought I understood. Now I saw myself, gasping, as the fire danced closer to my skin and the thin savannas of hair that protected what I called myself proved as effective as a fence against a raging avalanche. Or rather, I just watched and watched: I observed the scene with vacant eyes.

This could not be happening. When life ends, life is over, there is no thought, no analysis, no feeling, no hindsight. And yet I drifted away from life, entering a phase I had spent only a few seconds exploring. Where had I actually ended up, and what, really, was I?

While my body charred, I drifted higher, through the shifting temperatures of the floors, over the roof ridges, toward the sky with its veil of clouds, cumulus and cirrus. Higher, higher. It was as if I were still myself. but what was I if not for those brown irises, the soft rolls of my belly, that slightly offbeat gait which could be heard in the corridor from so far away it was as if I were marching in three-time? “Oh, the drummer is here,” said the girl in the stairwell, and I was, so to speak, on the same note, laughing at our inside joke because I was inside and not out.

But now, what did I look like? There must have been something soulful about my journey, I supposed. The religious had indeed spoken of such things: near-death experiences and other hallucinations, of how thousands, if not millions, of people have described preferring that enticing light over being ground down by the savage march of calendars.

The blue planet was no longer visible. The cardinal directions were thereby obliterated, unnecessary in the universe. There is no up or down. Up to what? Down to what? How could anyone be buried with their head pointed toward Mecca here?

For the first time, I began to wonder what would happen next, for the cosmos, by all reasonable accounts, was infinite. If I were to drift away like this forever, then I would have plenty of time to ponder my meager six decades as a body. In a few years I would probably curse myself for my inadequate sense of security, only to spend a few more lamenting what might have happened if I had, after all, demanded a divorce that one time, so that she would not later take me for granted. Since I wasn’t even man enough to make a single, modest, reasonable demand — “me or him” — there was always an either-or.

And now I drifted further into the other side, that part of existence I had never cared for except as a mere irritation. The ramblings of fools: astrology, witchcraft, spirituality, and the afterlife, if it could even truly be called life, for there were definitions for that: the need for water, the conversion of energy, and the possibility of reproduction. Can souls meet and beget other souls? Perhaps I would come to know that somewhere between now and eternity, but most likely not, I thought, as galaxies flashed by in my peripheral vision at ever-increasing speed, like signal lights on a highway on a December evening. Road work, an emergency call, or something else that did not concern me.

When I finally awoke, still entirely myself, as much as I could ever be. I was no longer composed of joints, or a hairline, or sensitive temples, but of a thin, green being made of chlorophyll, hungrily surging upward through the earth in search of the one thing I had always desired: the sun. Everything had become nothing but neck and toes, stem and roots, and it was, at last, spring.

I hope that some of this has resonated with you,

✦ jorgenlowenfeldt.se ✧ bagatellerna.se ✦

I loved this, and The Secret Pianist moved me deeply. The word that comes to mind is fragile. The music seemed to slide off the keys like tears. The hesitation to ask who the pianist was. And the pianist themself—the mere chance of being seen might have scared them into silence forever. How delicate this world is, where a pause, a hesitation, or the courage to reveal oneself can be as fragile as rose petals still clinging to the bud.

that slightly offbeat gait which could be heard in the corridor from so far away it was as if I were marching in three-time? “Oh, the drummer is here,” said the girl in the stairwell, and I was, so to speak, on the same note—laughing at our inside joke because I was inside and not out.

A story alone within a whole story