Letters from Seville

Featuring: Safari in the realm of wordlessness ✦✧ At New Year ✦✧ Zenonaut's Diary

It happened during a time in my life when I needed to ask myself what I truly wanted. And since the question arose in February, in Stockholm, the answer—much like it is for most people in that place at that time—was: to find another home, somewhere further south.

My second cousin happened to be in town, the question came up, and she said: Why don’t you ask my friend’s mother? She has a big house in Seville and could use some company.

That was the beginning of a tradition. I’ve, together with my children, now spent three winters in the house in San Jerónimo, and along the way, we’ve gained a Spanish family and several friends. Their openness has made this poor Scandinavian’s winters a bit easier to endure, and life there has also led to an abundance of literary text.

In this dispatch, you’ll find three of those bagatelles: one about a wordless party with syndicalists; another about spending New Year’s beneath the orange trees; and the third about a solitary space traveler—a piece I wrote at the very beginning of my stay, when everything felt unfamiliar and my lack of Spanish left me particularly alienated (as you’ve probably guessed, things improved over time).

The writing eventually grew into a Seville-based novel, Zenopolis, which I’m still in the midst of working on. Swedish readers can follow the editing process week by week, with the goal of sending the finished manuscript to a waiting publisher once the final dispatch has gone out.

Perhaps, in time, there’ll be an English version. Or even a Spanish one.

Warmly,

Jörgen Löwenfeldt

✦ Safari in the realm of wordlessness ✧

At the syndicalist party, I was one of only two English speakers—and he soon got bored of me. Since my only viable conversation partner also spoke the local language, he quickly found Spanish-speaking friends, while I shuffled through the crowd exchanging awkward glances that said, “Well, what can you do?”—like that shrugging emoji.

My presence soon became a source of stress for the others, who liked to see themselves as internationalists and now had to make an effort not to reveal that their antisocial behaviour wasn’t due to xenophobia but simple shyness. The terror that one of their comrades might overhear their hesitant attempts to engage me. I could sense all of this, so I figured I’d better busy myself however I could.

Silently devouring tapas lasted only five minutes, and I didn’t want to come across as either a drunk or a phone addict. So, stationed at the fringe of the party, I began examining each poster as if I were touring the Prado Museum with a secret audio guide. I studied the May Day brochures at the entrance like they were someone’s posthumous writings, discovered a misplaced wooden pitchfork in the umbrella stand—earning myself thirty seconds—before turning toward the bookcase lining the long wall of the room, shelves straining under the weight of books.

I’d already explored the meeting room and the kitchenette, and I understood this was where I’d have to make a discovery—just enough to occupy myself so the others could continue partying without having to account for my increasingly agonising safari through the land of wordlessness.

The shelves held classroom sets of textbooks, outdated encyclopedias, assorted tomes on property ownership and union work. Someone’s CD collection too—mostly local flamenco rock. Scattered throughout were novels, magazines with faded covers, and poetry collections. Some Machado and some Nakens, a bit of Lorca.

It wouldn’t be long before the partygoers realized I was wandering around pretending to read, like a child mimicking any language with enthusiastic conviction. Si, por favor, el madre. Best to find something fast.

The whole experience reminded me of that time in Japan in 2002 when I hadn’t seen my own alphabet in two weeks, and I devoured every snippet in the International Herald Tribune the moment I got hold of a copy. That thought bought me another minute and a half, but this time-nibbling approach wouldn’t hold much longer.

I was just about to give up and retreat to the bathroom for an extended visit when I spotted a small, handwritten booklet tucked between two identical manuals for a VCR. I understood even less of this than anything else. The letters looked like code. Dots placed over reversed characters. Lines piercing through U’s and W’s. N and B fused together. Some letters tilted at 45-degree angles. Even the symbols were new—tiny constellations of important scribble.

These lines of poetry, which seemed to follow haiku logic, interested me more than Lorca’s Spanish phrases, and I felt I had time to try decoding them. Pleased with my find, I brought the booklet to the armchair next to the printer, moved as if I were someone with a higher calling, and flipped through the pages with a naïve hope that I might suddenly be struck by total insight into this new language. That a trapdoor in my psyche would swing open, flooding me with previously hidden knowledge—like a fully written play awaiting its premiere.

For another full minute, I pretended to believe this. By that point, I had left the party’s periphery altogether. I wasn’t even present anymore. The people around me couldn’t see me, and I couldn’t see them. Maybe they’d moved on to sabering champagne bottles on the balcony, or were watching the much-anticipated short film premiering later in the conference room. Or maybe they were just still chatting, same as before.

I couldn’t tell anymore. My focus was absolute. I might as well have been on a meditation retreat on the far side of the moon—or in my bed at home, blinds drawn tight, earplugs screwed in. There was something almost erotic about the letters of this language, which I imagined could only be read by one person in the world. I pictured it having been invented by a young girl, to keep her mother from reading her diary. And the knowledge had stayed useful well into adulthood, when the language became her go-to for anything private. Like a habit no one had thought to break.

Maybe this short poem, in five-seven-five syllables, expressed unrequited love for a colleague—something she printed so he could keep the words close without understanding them. Like a spell. The papers were yellowed enough that the girl was surely more crone than woman by now.

I raised my eyes and scanned the clusters of people leaning in toward one another. Men, women, girls, guys, idealists and significant others. Some with unruly hair, others bald. Some tattooed, others dressed like lawyers.

Which of these three silver-haired women—yes, three—had written this? I focused on them in turn, waiting for someone to flinch at the sight of me with the booklet in my lap. Of course she would reveal herself the moment she saw me. A shiver of recognition, too deep for anyone to hide. Only—no one was looking my way. By now I had been collectively forgotten.

That’s when I heard a sound from the hallway—a murmur of words and sentences that were suddenly comprehensible. Like I’d been rudely yanked from the jungle of dreams. A “Sorry I’m late,” in a thick Cockney accent was my alarm bell.

And then, like a long-overdue babysitter, the polyglot private tutor from Bristol strode my way, gave me a firm handshake and asked, “What are you reading, mate?”

I snapped the booklet shut, returned it quickly to its place between the VCR manuals—as if I’d just finished Jumanji and couldn’t explain, even if I’d wanted to—and said as casually as I could:

“Oh, it was nothing. Nothing at all.”

✦ At New Year ✧

Of all the places I’ve woken up, this one feels like a dream. Still Seville. Alamillo Park. A black-and-white-spotted cat seeks contact but avoids people. The grass. I lie down flat as if I’m fainting myself awake. The sun fills me from the inside. The book lies half-read, recovering. From the bushes, a horde of birds. They imitate rainforest and crickets: scratching, hatching, chattering an endless gossip that might matter. Spanish human voices from families on rental bikes. They roll through the green tunnel into path. Close, yet gone. My own children on an expedition in other clearings. Talking squirrelishly about this and mostly that, and then back to this again—beyond my event horizon. Instead: distant sirens, alternating with the muffled groan of traffic. Over there, past the olive grove, the bridge can be glimpsed. The resting harp whose load-bearing strength is said to be doubtful. One day the strings will snap and fling the roadway into the universe. But now, more here here: someone is rinsing off their fireworks. Someone else is using up their firecrackers. Tentative crackles and the roar of war. It’s New Year’s Eve in the city without seasons. The birds keep chattering. The brain is quiet.

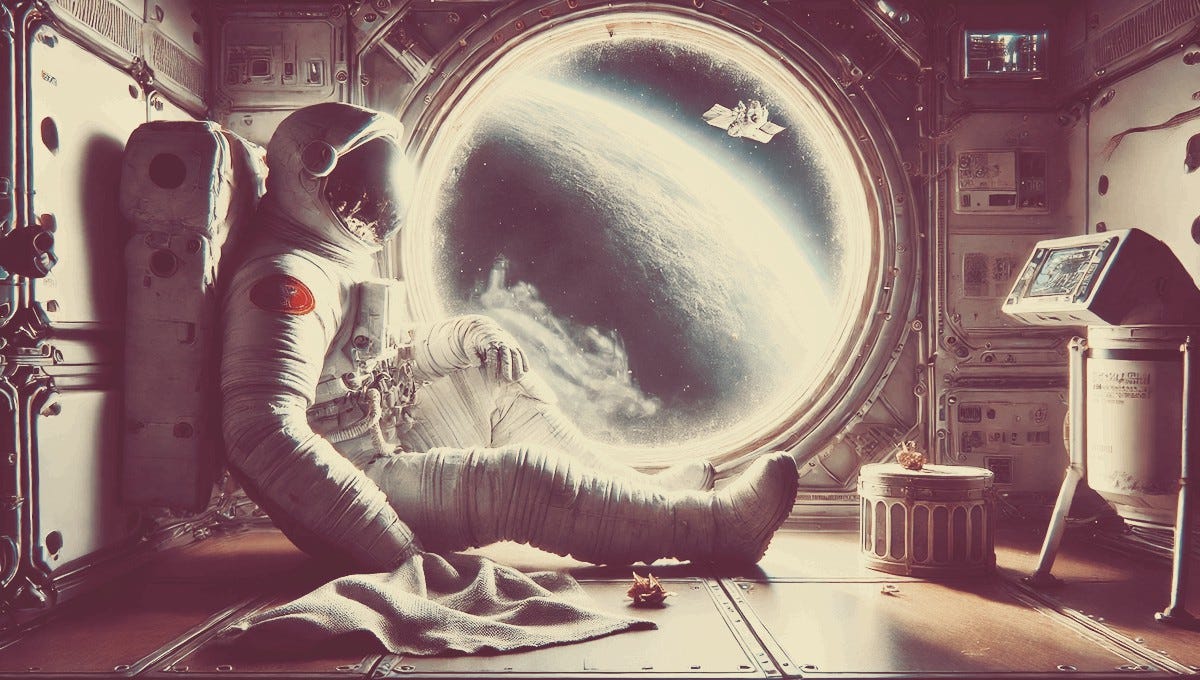

✦ Zenonaut’s Diary ✧

At launch, they called me the Union’s hero. The Emperor addressed the people, speaking of my vital mission as the intergalactic high guard. I was tasked with watching over the empire. Orbit after orbit, day and night. Even insomniacs could look up at the sky and see a shining dot. That was me, aboard the station: Zenonaut Number One. Thousands, maybe millions of people had already waved to me, then drifted back to sleep.

But now, things are happening down there. Things I can’t do anything about. I don’t know much about politics, but I ask myself: why change something that works so well? The salary landed in the account every month, the Emperor was the Emperor, and soon his son, the Regent, would take over. Sure, the police could be bribed, but they were our police, they looked the other way in a reliably bureaucratic fashion. And all of us—myself included—were issued clean, pressed uniforms. There weren’t a bunch of elections. Bread was bread. Everything was in order.

Now it’s just chaos. I follow the TV news from orbit. Stores looted, tanks waiting outside parliament, the flag flown upside down. Crowds shouting wildly on live broadcasts, expressing opinions you weren’t even allowed to think before.

Up here on the station, everything remains unchanged. I keep orbiting, staring into the sun nearly all the time while missing it deeply.

Suddenly, the new rulers call from Earth. They’ve already installed themselves in every palace and city hall and handed out fancy titles to one another. They’re not interested in a space program anymore—there are more pressing matters now, like the cable car system and mold remediation. They say: You’ll have to stay up there a while longer, until we can scrape together some funds. You know, it’s democracy now. We have to think things through.

I say to them: One day on this space station is hard internal labor. A week is tough. I don’t dare think about a month. How do you expect me to survive six?

There’s a pause. There always is while the signal travels, but this time it feels even longer.

Then another voice says: We don’t have the resources, you know. It is what it is. Your food rations should last. You’ve got books. Read. Enrich yourself in the world’s knowledge. We’re fighting for our lives down here. You can lean back and enjoy. You’re not the one to pity.

I don’t know what to say, because answering would reveal something embarrassing. So I say:

Yes, I hear you. I’m trained for this.

That’s the spirit, they say down there.

Every time I glance toward the planet, I see a part of my vast realm—from the Sewer Ravines to the Icebreakers. I think: How are they doing? The system is collapsing and the people are left to fend for themselves. But how could my mother be sold at a market? She can sew, she can cook, but she knows nothing of commerce. The others might learn. But her?

Six months is a long time to be alone while everyone else lives their lives. I end up fantasising a lot. It would almost be easier if all life on Earth had perished—then I wouldn’t have to worry about them. But it is what it is. What am I supposed to do? Force them to come get me? How? I’m at the mercy of the new rulers.

Then again, I’m not easy to rule. So I start embroidering. It’s against protocol, but it makes me think of my mother. She showed me once how it’s done. It’s not hard, she said. The hard part is doing it well, not doing it at all. And I can do it. Doesn’t have to be good. My future biographers will wonder what drove me to use fine mouliné thread even though I had to double up on bandages so the blood from the wounds wouldn’t stain the fabric. In the beginning, little red droplets floated through the station’s microgravity. I had to catch them with empty tuna salad containers. Not very appetising, but blood can damage the equipment. Up here, liquid always finds its way into the machine’s heart.

I watch TV almost constantly. I feel shackled, want to descend and fight. Probably everyone feels that way. So they show other things: soap operas, game shows, reports from the world expo in Spain. The heat is intense. Every street corner has devices that spray mist, as if humans were plants. Nations show off their pavilions. There’s Sweden, there’s Brazil, there’s Morocco. I know nothing about these places. I’ve never longed to go there. It’s like the new rulers want us to dream of elsewhere, to desire things we don’t already have.

The biggest pavilion is called Futuro. In the future, people will have forgotten me, because I belonged to a country that forgot itself. But I’m sure many will want to hear my story of circling the Earth in solitude—because they too have felt alone. I’ll say I felt like the child staring out the window, watching the other kids play in the courtyard.

Sometimes I call Earth for no real reason. I make something up, say a lever is starting to wobble or that the toilet pump is making noises—I don’t want to risk floating feces. It’s obvious what I’m doing, but they let me do it. I ask how the weather is in Zenopolis. They laugh. It’s like they don’t notice the weather at all. Even though I know they’re just sitting around.

I get that there’s no space program anymore, but still, people are assigned to it. They’re not paid. Instead, they sell stuff on the black market. Satellite models or rocket fuel in jugs—anything they can get their hands on. Someone’s talking about turning the rocket hall into a nightclub. Charge admission. Sell gin. Up here, I have no one to sell to.

When I call too often, they remind me I should read a book or something—like an annoyed parent would say. Though I think they suspect I’m not really the reading type. If asked, of course I’d claim I’ve read Zee-Stiernborg, Xi-Offerman IV, and, if a southerner asked, even Xú-Alexis. It’s not true. The truth is I struggle with words—always have, even back in school. It became my secret. But numbers came easy. How things fit together, how to dismantle and rebuild a generator or a steam engine. My hands have always served me well.

Now I have no choice but to search the bookshelf. I’ve embroidered so long my fingers are numb. And I’m out of bags. I find political pamphlets on property rights, some manuals for the docking station, and a small booklet of short stories another Zenonaut brought and left behind. It’s all mine now. If I’m ever rescued, my final act will be to send the ship off course. In billions and billions of years, perhaps some alien will find my blood in the tuna containers and build a replica of me.

One story in the booklet is about a man who writes. It’s kind of silly—writing about writing, or reading someone writing about writing—but beggars can’t be choosers, as an American once said in a strip club (I looked it up afterward). The author says there are other values than ambition, other pursuits than efficiency. He claims fantasies are necessary—not to balance budgets, but to deal with life. He brags about smoking and drinking. Writing, smoking, drinking. He meets women and caresses breasts. They see drive-in movies in his Chevy. The women can’t get enough of him.

I probably shouldn’t have read that. For weeks afterward, I dream of driving on the highway. I spot an exit ramp but I’m going too fast to make the turn. The car flies into the shoulder and beyond. That’s when I wake up—when it all comes to a halt. A pine tree, or a ginkgo, or a bus. I don’t know, because in the dream I’m already dead.

When I regain consciousness, I decide to go back to numbers and hands. I start embroidering again. It goes better this time—no bandages needed. It’s as if I learned while doing something else. My mother would’ve had a stroke if she knew what I was doing up here. But she would’ve been proud too. The stitches lie neat and close. And she would’ve said that at least somewhere in this world, there’s order. That’s definitely what she would’ve said, I think, hearing her voice echo in the space within me. Just like I was on Earth.

I hope that some of this has resonated with you,

✦ jorgenlowenfeldt.se ✧ bagatellerna.se ✦

A wonderful read--I especially loved Safari. As an introvert, your description of the painful party made me laugh: "Silently devouring tapas lasted only five minutes, and I didn’t want to come across as either a drunk or a phone addict. So, stationed at the fringe of the party, I began examining each poster as if I were touring the Prado Museum with a secret audio guide." So apt!

I loved the mix of these three so joyful to read. To the 1st one I related the most, the 2nd one was sort of a charming rest before the 3rd took over my interest... might be cause I'm currently reading "The Book Of Strange New Things" by Michel Faber (for the 2nd time). Reading it, I knew I have to write my own sci-fi novel.